The campaign for the return for ‘stolen’ African art, like the Benin Bronzes, has spanned decades. Thousands of artifacts looted from African cities over a century ago can easily be found in European and British Museums and institutions. But, the homecoming of looted artworks looks like a possibility now. A new market for African arts has emerged. Is that worrisome?

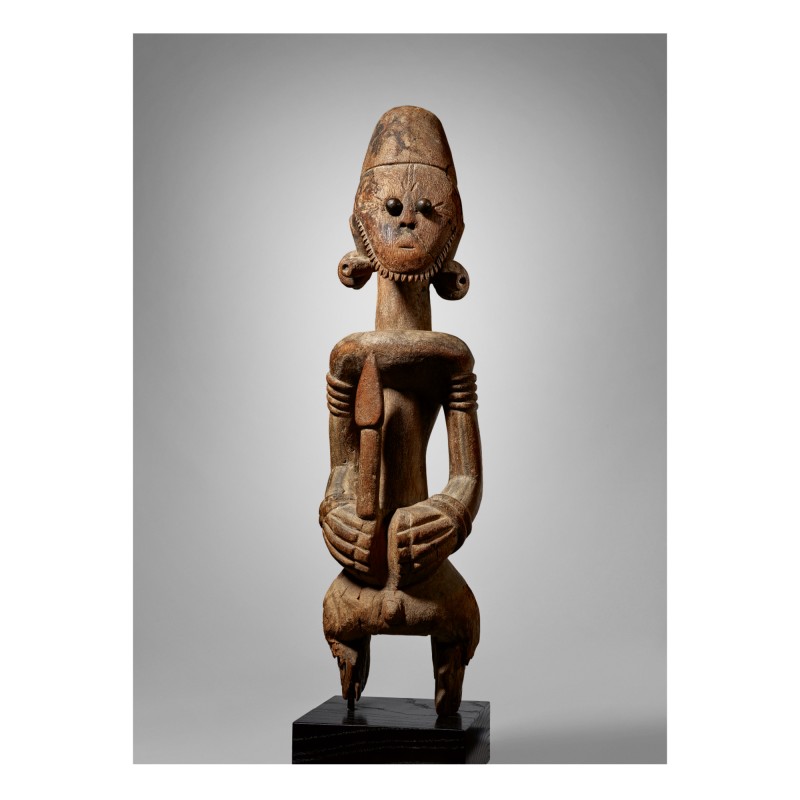

Christie’s, the British auction house, had a curated “Arts of Africa, Oceania and North America” sale. The African art section included works from an Important European Private Collection, including a major Urhobo statue from Nigeria, a museum-quality Igbo couple and beautiful masks from the Fang, Chokwe and Punu.

A Princeton art history professor said the Igbo figures were stolen and called on Christie’s to halt the sale, but it went ahead with it. “These artworks are stained with the blood of Biafra’s children,” wrote Chika Okeke-Agulu, in an impassioned Instagram post calling for a halt to the sale of two wooden statues made by the Igbo people of Nigeria. He said that Christie’s Igbo figures were among many artifacts stolen by intermediaries at the behest of European and American dealers and collectors, such as the renowned French collector Jacques Kerchache.

In a statement before the auction, Christie’s responded to Okeke-Agulu’s Instagram post, saying the sale of the statues was legitimate and lawful. “There is no evidence these statues were removed from their original location by someone who was not local to the area,” the statement said, adding that Kerchache never went to Nigeria in 1968 or 1969 and that Christie’s had worked to reassure all enquiries regarding the provenance and legitimacy of the sale.

The Brussels-based dealer, Bernard de Grunne, who sold the sculptures in 2010 to the seller at Christie’s, wrote, according to New York Times, that “We cannot connect them with the chaos caused by the Biafran war, as we do not know when precisely they came out of Nigeria. They could have come out anytime between 1968 and 1983.”

“A reverse argument can also be made that these great works of art were saved for the world to admire at that point, instead of being burned and destroyed during the war,” he added.

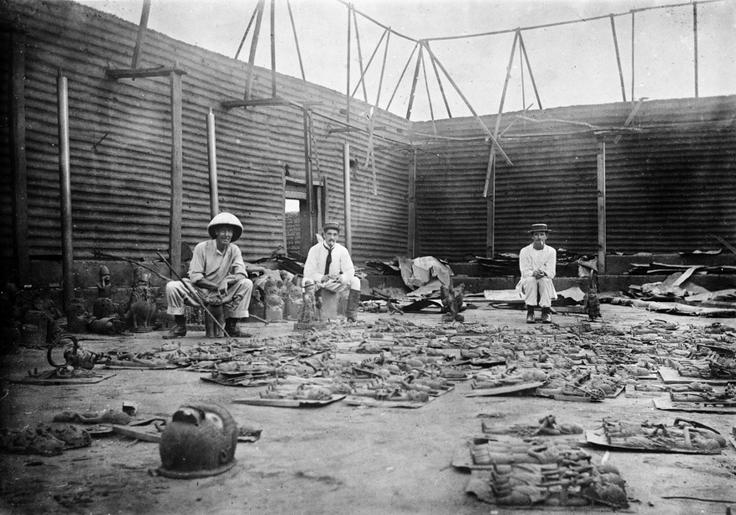

Christie’s offered Benin Bronze plaques similar to Bronze plaques from the St Petersburg and Berlin Museums; artworks with a well-documented history as part of looted artifacts from the Royal Court in the invasion of Benin City in 1897.

The British-founded American auction house, Sotheby’s, on June 30, had an ambitious sale of “The Clyman Fang Head,” a statue with an estimated value of between $2.5 million and $4 million, from the collection of Sidney and Bernice Clyman. A total of 32 African artworks from the collection were offered across a series of auctions at Sotheby’s.

Auctions of valuable African artifacts, some of which could be identified as candidates for repatriation to their lands of origin by activists, would be controversial in normal times, but particularly so during the ongoing global pandemic and its attendant economic after-effects. Sotheby’s and Christie’s moved the auctions online for this reason.

Sotheby’s said in March it has seen an expansion of interest in African art auctions with a more diverse customer base online.

A lot of valuable African art is not on the continent, including statues and thrones, with hundreds of thousands of historical artifacts domiciled in Belgium, the UK, Austria and Germany.

A French report, commissioned by President Emmanuel Macron in 2018, called for a change in French law to allow the restitution of cultural works to Africa. In a meeting with students in Burkina Faso in 2017, Macron said “Africa’s heritage must be showcased in Paris—but also in Dakar, in Lagos, in Cotonou. This will be one of my priorities. Starting today, and over the next five years, I want to move toward allowing for the temporary or definitive restitution of African cultural heritage to Africa.” The report estimates the British Museum alone has a collection of around 69,000 works from Africa.

In 1897, British troops invaded Benin and destroyed a large portion of the southern Nigeria city; looting 4,000 works of art including the famous Benin brass heads and bronzes. Today, the British Museum in London has about 700 Nigerian historical artifacts with around 100 of them displayed in an underground gallery.

The clamour for the necessary of African artifacts has intensified, forcing the British Museum to “lend” some of the artworks to a proposed new museum in Benin City billed to open in 2021. But, it has been stated that unless it could be proven that objects were obtained legitimately, they should be returned to Africa permanently, not on long-term loan.

Some of these artworks are religious monuments and represent a fading part of African culture and history. But the artifacts are already a part of a global ecosystem that is seemingly moving on without Africa. For Prince Yemisi Shyllon, a Nigerian art collector, the value ascribed to many artifacts taken from Africa exist because of their current location.

“There is a working industry and infrastructure to support the works of art. The moment those works come back to our control, they will lose value just like the ones that are here. The conversation moving forward should be to claim ownership and then claim annual royalties to these works of art even as they remain where they are,” says Shyllon, according to Quartz Africa.

But Prof. Okeke-Agulu might not agree with this suggestion, as he continues to use his voice calling for the repatriation of African artworks in European and American collections that are thought to have been acquired through colonial exploitation or illegal looting.

Shyllon’s suggested methods might be just the way forward with this, until Africa begins to revive it’s dying museums and sustain a maintenance culture.