While we agree that Africans can only observe than participate in the U.S. Elections, it is important to note that in a few days, the U.S. would have elected a new President in office, or will continue with incumbent President, President Donald Trump.

The U.S and Africa ties

In an article by Howard W. French for WPR written in January 2020, titled America’s Downsized Relationship With Africa Is About to Go Totally Adrift, he pointed out that since the end of the Cold War, American relations with Africa have been characterised by a single, powerful trend: disengagement. Its direction has been so constant that it is tempting to think of it as a fixed given, but that would be a mistake. In reality, over the past three decades, this troubling trend has only accelerated.

In a study titled “US-Africa Relations: In Search of a New Paradigm”, George Klah Kieh described the US-Africa relations in his background of the study. U.S.-Africa relations have evolved in two major phases: the final stage of the “old globalisation” (1946–1990) and the “new globalisation” (1990 to the present).

“At the beginning of the final stage of the “old globalisation,” the totality of the African continent, with the exception of Ethiopia, Liberia, and Egypt, was under the imperial control of Britain, France, and other colonial powers. Based on the restrictions imposed by colonial imperialism, the United States used its influence as one of the emergent “superpowers” to pressure the comparatively weak colonial powers to grant “independence” to their colonies. American action was not driven by altruism and the associated concern for the welfare of Africans. Instead, it was propelled by the desire of the United States to make the continent’s various natural resources available to the economic wing of the American ruling class for pillage and plunder.”

He quoted Harry Magdoff who asserted that:

“American foreign policy is not designed to help improve the material conditions of ordinary citizens. Instead, it is driven by a desire to maintain as much of the globe as possible for private trade and private enterprise based on the prevention of competitive empires from acquiring privileged trading and investment preserves to the disadvantage of U.S. business interest, and wherever feasible, the attainment of a preferred trading and investment position for U.S. business, and the promotion of counter-revolution, which is hoisted on the abortion of incipient social revolutions and the suppression of social revolutions in progress.”

In Kieh’s study, he stated that “… the government of the United States took two major interrelated measures. First, over time, it forged patron-client relationships with some of the most tyrannical regimes on the continent, including arap Moi (Kenya), Barre (Somalia), Doe (Liberia), and Mobutu (Zaire). Washington ignored the increasing human rights abuses and political mismanagement by its various client regimes. Instead, it provided them with, among others, weapons, which they used to suppress dissent. The other major step taken by the United States was the undermining, and in some cases the removal, of regimes that sought to cater to the needs of the members of their respective subaltern classes. For example, American and Belgian imperialism collaborated in ousting the regime of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo. Similarly, American and British imperialism worked in tandem to encourage a military coup that removed Kwame Nkrumah from power in Ghana. Particularly, Nkrumah’s call for the establishment of “United States of Africa” was antithetical to the United States’ imperial agenda on the continent. With the end of the “old globalisation,” including the Cold War, which constituted one of its major dimensions, the United States is now constrained to repackage its imperial agenda. One of the significant outcomes is the intensification of the democracy promotion rhetoric.

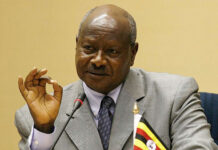

That is, the United States is attempting to convince the subaltern classes in Africa that it is committed to the establishment of democracy on the continent, while continuing its policy of supporting various authoritarian regimes there— Kagame (Rwanda), Mubarak (Egypt), Museveni (Uganda), and Zenawi (Ethiopia), among others.”

As Vassilis Foukas and Bulent Gokay observe, “Imperialism has often clothed itself in noble rhetorical garb, claiming to pursue its hegemony for the good of the nation or even the good of humanity. Interestingly, the election of Barack Obama as the president of the United States created the illusion among some Africans that the United States will abandon its imperial agenda and support the establishment of democracy and the promotion of socioeconomic development in Africa. On the contrary, the reality is that President Obama simply represents the “new face” of American imperialism, which is characterised by, among other things, the abandonment of the use of bellicose language that was a major hallmark of the Bush regime.”

Thus, as Horace Campbell aptly asserts, “The American ruling class [will continue to view] Africa as a treasure trove to be plundered.”

The U.S. Elections in 2020 and Africa

Joe Biden and Donald Trump are the two contestants for the Presidency in the US running under the Democratic Party and Republican Party respectively. For more than a year, the contest had begun but currently, eligible Americans have headed to the polls. Both candidates confident they will come out victorious. But why does whoever wins matter to Africa?

Howard W. French in his article had this to say – “As the civilian bureaucracies that are supposed to lead American foreign policy have steadily disengaged from Africa, they have been eclipsed by the Pentagon. Of course, every few years Washington still rolls out a tepid rebranding of its low-wattage trade and investment policies toward the African continent. The Trump administration’s version is something called “Prosper Africa.” But when it was unveiled at a summit in Mozambique last June, the truest reflection of prevailing American attitudes toward the continent came from the fact that Washington couldn’t even muster a Cabinet secretary to attend the event.“

“It is important to stress that this is not a problem unique to Trump administration dysfunction. According to the traditional rules of diplomacy, a country shows its commitment to foreign partners by servicing the relationship. When a relationship is healthy and constructive, this means frequent, high-level contacts. China has made a priority of its relations with the African continent in this century. It is not just a matter of fast growth in trade and investment, but can be readily seen in the way Beijing has serviced its African relationships. China’s premier and the head of the Chinese Communist Party—the country’s top two leaders—have each visited Africa almost annually for years now, as do numerous other Cabinet-level and other senior Chinese delegations.

Going back to the continent’s independence era in the late-1950s, the U.S. has never accorded Africa such consistent high-level attention. But since Washington’s civilian disengagement began after the Cold War, Africa has been treated more and more like an essentially military and security problem to be managed strictly at arm’s length. What that has come to mean in practice is that the U.S. engagement with Africa has gradually come to be led by the American military’s Africa Command, based not in Africa at all, but in Stuttgart, Germany.”

If Trump wins, the status-quo remains. But if Biden wins, we could have the same situation as the Obama administration.

But will that be the case? From all that has been going on so far, the election is an internal affair for the US.

In an Article by Patrick Smith, titled “Stakes are high for Africa in US presidential election”, he mentioned that “Africa has not figured in any of the presidential and vice-presidential debates, or in much of the campaigning. Yet it has a serious stake in the outcome as shown by a clutch of Trump administration actions in the last few months.” Here are a few of them;

- Fight over the Nile

The most egregious is President Trump’s attempt to strong-arm Ethiopia into accepting a deal with Egypt in the long running dispute over a hydro-power dam on the Nile. Earlier this year, talks in Washington DC were brokered by US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, on instructions from Trump, in a move designed to show that the White House could handle international diplomacy. On this occasion it couldn’t. Affronted by what they saw as an ultimatum from Mnuchin to sign a lop-sided agreement on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, the team sent by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed withdrew from the talks. Last month, the Trump administration suspended US aid to Ethiopia, attempting to ratchet up the pressure. Hell hath no fury like a President seeking re-election and diplomatic validation.

- Shoving Sudan to recognise Israel

Just as problematic have been the Trump administration’s negotiations with Sudan over its removal from Washington’s list of state sponsors of terrorism. Before that could happen, Washington insisted that the Sudan government would have to pay $335 million in compensation to US victims of terrorist attacks aided and abetted by the ousted Islamist regime of Omer al-Bashir.

Gilbert M. Khadiagala in his article, Contextualising the impact of the 2020 US elections on Africa, pointed this out – “Claims about Republican marginalisation of Africa and Democratic championing of African causes has, for the most part, turned out to be inaccurate. Since the end of the Ronald Reagan administration, subsequent Republican administrations under George H.W. Bush (1989- 1993) and George W. Bush (2001-2009) matched, and in some cases, outperformed the democratic administrations of William Clinton and Barack Obama. The initial humanitarian intervention into Somalia in 1990 under the elder Bush and the launch of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) program in 2003 under the younger Bush were among the landmark Republican decisions. By contrast, the Rwandan genocide occurred under the watch of President Clinton and some have criticised the Obama administration for deepening the militarisation of US-Africa policy. Substantively, therefore, Africa’s popular preferences for Democratic presidents are always oversold.

This is why we need to disabuse ourselves of the prevailing assumption that a Democratic Party win in November 2020 will result in shifts in US-Africa relations,” he stated.

What it means for the young Africans

The US focus on youth engagement stems from the realities of Africa’s demographic shifts and the potential it offers. Recognising that Africa’s youth population will double in 2050, the Obama administration championed youth leadership in its engagement with the continent. The Young Africa Leadership Initiative (YALI) is a product of Obama’s efforts and may remain as a key platform in US-Africa policy. The Trump administration followed upon this through the establishment of the University Partnership Initiative (UPI) to help strengthen existing ties between US and African universities. (Gilbert. M. K.)

Should Africans give this election that much attention?

Gilbert had this to say: “As attention to the US elections intensifies, African leaders, policymakers, academics and scholars must actively guard against the dangerous fixation with Big Man politics. A preoccupation with who is going to win in November invariably obscures other significant players who routinely shape US-Africa policies and who deserve more attention than the occupant of the White House. More pertinently, it prevents the articulation of collective African voices and positions around long-term relations with the US. Rather than working to forge African positions on trade, terrorism, immigration and other issues that have more longevity and would better prepare Africa for effective engagement with the US, the focus is, instead, on elections that Africa does not have any leverage over.”

As much as the United States elections have little to do with Africa. We cannot rule out the fact that whoever comes out tops in this election will have an impact on the African continent, whether it is political or not.